TSTN-046

LOVE deployment configuration on k8s.#

Abstract

Here we describe the LOVE deployment configuration used on k8s. We start with a brief description of how LOVE works, its different components and communication workflow. From that we describe how the system is deployed on k8s, the different services that are part of the deployment and their role. We proceed with a description of the issues we currently observe with the system as the number of users and traffic from the control system increases and finalize with a few ideas for future improvements.

Introduction#

The LSST Operators Visualization Environment (LOVE) is the main interface for users to monitor and control the Rubin Observatory Control System. This is a React based web application that powered by a Python Django backed. Below is a high-level overview of the different sub-components of the system.

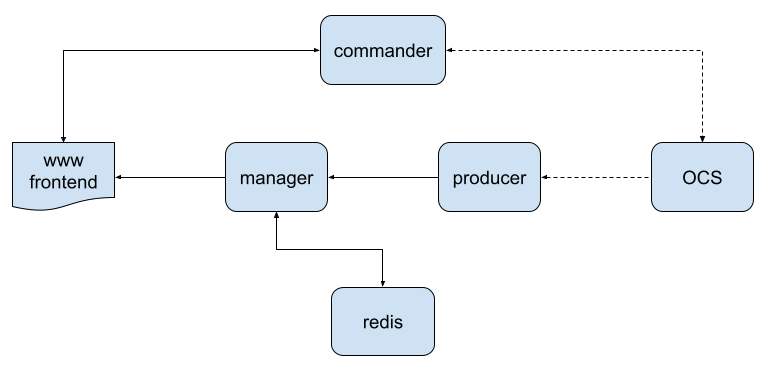

Fig. 1 High-level overview of LOVE’s architecture. Arrows indicate the direction of the communication; the dashed lines represents SAL traffic from the observatory middleware whereas solid lines are mainly TCP/IP socket communication.#

In the architecture diagram above, the OCS represents the Observatory Control System; these are all the components (CSCs and Scripts) that communicate using the SAL middleware.

Next to the OCS are two LOVE components; the commander and the producer.

The commander is a simple Python web application that consists of a web server that can communicate with the observatory control system through the SAL middleware. Clients can request CSC commands to be executed by the commander, which executes them and sends the results back to the client. This communication is done via http requests.

Producers, on the other hand, are designed to read data from the OCS (e.g. telemetry and events) through the middleware. When they start, a producer will subscribe to the data for an individual component on the system and start listening for new data. Separating them by CSC allows load to be distributed between several producers instances. Telemetry and events are treated differently by the producers; telemetry data is pooled at a set frequency, while events are listened to asynchronously. Furthermore, the producers will continuously attempt to connect to an http server and, once connected, will send any data they receive from the control system.

The manager is a Python Django application. At one side, they act as a connection server for the producers and receive the producer data. When the manager receives data from a producer it writes it to a Redis server. On the other hand, managers act as a server to broadcast data. When data is written to the Redis server, the manager broadcasts it. This is done by relying on Django-channels backed by Redis (see this article for an explanation on how Django-channels works). The manager also retrieves old historical data from Redis to send to new clients when they connect to the system.

Finally, at the user side, there is the frontend application. As mentioned above, the frontend is a JavaScript React web based application. The frontend connects to the manager via a socket to receive data from the control system and to the commander to execute commands. The connection with the manager is mainly unidirectional (though we should note that the frontend does send http requests to the manager for some data), with data flowing from the manager to the frontend. For the commander data flows in both directions; the frontend sends requests to the commander and the commander sends the response back to the frontend.

Kubernetes Deployment Configuration#

LOVE Kubernetes deployment configuration is divided in 4 different applications. There is a main love Application that is a custom resource definition (CRD) kind of application provided by ArgoCD, designed to group the LOVE’s services. Inside it there are four applications; love-commander, love-manager, love-nginx and love-producer.

Three of these applications (commander, manager and producer) are easily identifiable in LOVE’s architecture diagram above and their roles are described in the introduction session. The missing piece is the frontend application which, as described above, runs on the user’s web browser. The application consists of a series of static assets (html and JavaScript) that are delivered to users by the love-nginx application when they connect to the LOVE services.

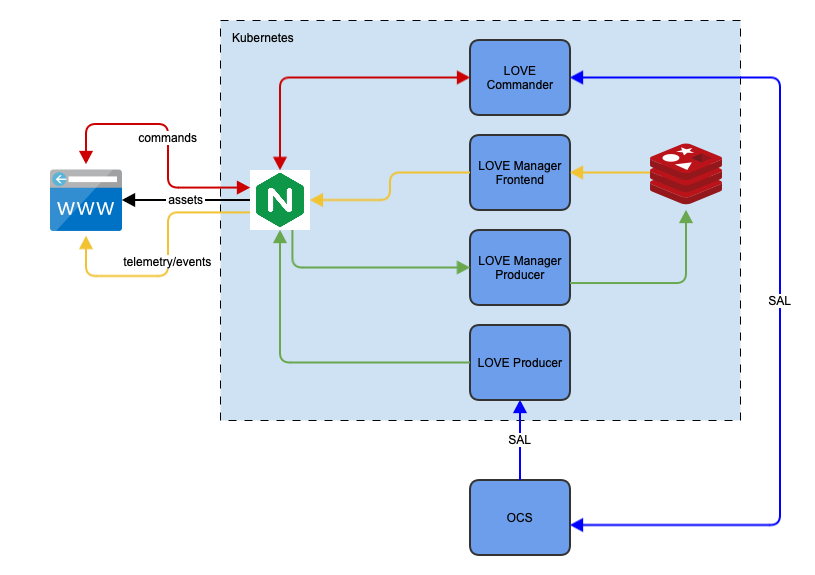

The love-nginx (pronounces “engine x”) application also works as a http proxy server, routing connections from the front end to the different backend services; commander and manager. It also serves as a proxy between the producers and the manager. Below is a diagram showing the interaction between the different components of the system.

Fig. 2 High-level overview of LOVE’s deployment services. Arrows indicate the direction of the communication, colors are used to identify the data source.#

One detail not captured in the deployment diagram above is the multiplexing of the managers and producers. As mentioned above, producers are split on a per-component basis, meaning there is one instance of the love-producer for each CSC in the system.

The managers, on the other hand, are subdivided in a more complex way. One thing to keep in mind when it comes to scaling the managers horizontally is that they play two different roles in the system; they receive data from the love-producers and they send data to the frontend. Furthermore, these two roles are completely independent of each other; the manager receives data from the producer and writes that data to Redis and it streams the data from Redis to the frontend. This allows us to split the managers into the producer and frontend roles (henceforth referred to as manager-producer and manager-frontend), each of these roles requiring different scaling strategies.

The initial Kubernetes configuration had split the manager-producer and the manager-frontend in two auto-scaled replica sets. Each replica set consists of an initial minimum number of pods, and the auto-scaling service is responsible for starting more pods based on the average CPU utilization across all pod.

Initially the same strategy was applied to both sets of managers; start with a reduced number of pods and scale up as load increases. However, given the way the manager-producer works, one can imagine that this strategy would not be appropriate. Basically, each producer connects to a manager-producer once, and will retain that connection for the entire duration of the process. As the load increases from increasing producer traffic, more manager-producer pods would be created but none would get any load as the connection with the producers were already established.

We now modified this strategy for the manager-producer to rely on a fixed number of pods. We also create specific manager-producer instances for critical components of the system; M1M3 and the ScriptQueue. The M1M3 is the component that produces the highest traffic on the entire system. We felt like relying on an auto selection procedure that would not provide the best strategy to handle its load, and decided for a dedicated manager-producer.

The ScriptQueue is one of the most user-critical components of the system. As such we also decided to provided a dedicated manager-producer set. Since we currently have 3 instances of the ScriptQueue running at the summit, we created a manager-producer set with a replication factor of 3 and let the load balancer automatically route the connection. If we see that this is causing the connections to concentrate on one or two of the manager-producer pods, we can also manually select them, as we do with M1M3.

For the remaining components of the system, we created a manager-producer with a replication set of 10. Some early experiments show that this works well. As we gather more information about the behavior of the system we can resize this pool or create additional dedicated resources. For example, one component that might also require a dedicated manager-producer is the MTMount, which contains the seconds highest throughput of the system, behind M1M3.

Known Issues#

The following is a collection of issues we still identify with the system after we did the last revision of the deployment configuration.

High load per view#

One thing we noticed in the LOVE deployment is the high load on the LOVE Manager Frontend per view opened. A rough measurement suggests that for each new browser window that opens a view on LOVE we see a load of about 80% CPU usage in the LOVE Manager Frontend. We have not done a detailed analysis on this metric so it is not clear how it scales with the type of view and the amount of data required by each view.

Auto-scaling issues#

Given the long-lived nature of the connection between the manager and the frontend, this represents a real challenge for the autoscaling algorithm. Once several incoming connections are received they are immediately routed to existing managers instances. This causes the load to spike and the auto scaler to start bringing more managers up. However, none of the existing connections are rerouted, because the frontend and the manager are already mated. Even though new connections might get routed to the new pods, any existing connection will remain on the previously existing pods, which ends up overloaded.

Load balancing#

This issue is related to the auto-scaling problem reported above.

Bringing up new instances of the LOVE-manager-frontend is only part of the auto-scaling/load balancing act. Once new instances are brought up, traffic needs to be routed/rerouted to them, in order to create a more reasonable load on the system. However, what we experience right now is that a few instances are heavily loaded while others are mostly idle.

This effect is actually related to how the load balancing on Kubernetes is configured. Right now we rely on a ClusterIP Service to route the network traffic to/from the LOVE manager-frontend which, in turn, rely on IPTable rules for network routing.

The default rules are quite simple and are written automatically by the Service. A description can be found in this article.

One main issue we face here is that there is a considerable delay between the time it takes for the auto-scaler to startup a new instance of the LOVE manager-frontend, for the ClusterIP Service to detect that this new instance exists, for the ClusterIP to rewrite the IPTable rules and for the new rules to take effect. All during this time, new connections are routed to the previously existing systems. In fact, we have noticed that there is a period during this process in which the connectivity between the manager-frontend and the frontend drops and no data is sent to the user. We believe this happens when the service restarts the IPTable service, which temporarily halts all communication.

We currently have no solution to this problem.

Redis Overload#

Another issue we have identified with the system is that, as time goes by and more data accumulates in the Redis service, we start to experience considerable lag. This seems to be due to the fact that the topics for Scripts executing in the ScriptQueue create entire new sets of table for each new Script executed. This is because the system treats each Script as an individual component of the system, rather then aggregate them into a single table.

There is also the fact that the traffic to feed the system is coming entirely from a single instance of Redis and, as more views are opened, the more outbound traffic Redis has to cope with.

We have been experimenting with adding a Redis cluster, instead of a single instance. This would allow us to split the traffic into more than one Redis instance.

Furthermore, we should also try to design a more clever way to store the Script data. For now, we have been dealing with this issue by cleaning up old instances of Scripts for which the data is no longer needed.

Resource Material#

The following is a collection of articles that were useful during this exploratory work.

Introduction to Django Channels, explain how the technology that powers the love-manager works.

Load balancing and scaling long-lived connections in Kubernetes, explains how load balancing works in Kubernetes.

Turning IPTables into a TCP load balancer for fun and profit, explains how IPTables can be used to create a load balancers. This is, for example, how ClusterIP handles load balancing.

Kubernetes: Service documentation, documentation on the concept of “Service” on Kubernetes.

Kubernetes: Service ClusterIP allocation, documentation on the ClusterIP Kubernetes service.

Kubernetes: Network Policies, documentation on Kubernetes network policies.